We did it twelve times — made love, all of us, to one another twelve times, the two of them doing everything two people could do to me twelve times. I was going to say only twelve times, but it wasn’t “only,” was it? It was wonderful.

I began, last night, at the beginning. The rule was I had to tell the truth, and I had to tell him everything. I could start where I liked. I told him the story every night; he asked for it, for some version of it, every night. Sometimes I left out a detail so he would prompt me, and thus participate after a fashion. “The inevitability of orgasm?” he might say, and I would say “The way she moved her hip into me first.”

Sometimes I changed their names. Names were not the details that mattered to him. What mattered was the most refined particularity of our actions, and the declarative nature of my narrative. He did not want me to use language that said anything other than what it was. For me, I mean. Well, for them, her. All of us.

“I want you to give me points on the body — nuanced, subtilized, exact,” he said.

“I want fine-grained diction in the reportage, and I want it to be plummy. I want the ring of inexpressible reality — yet lyric.”

“Were there photographs?” he asked, knowing that there were.

“Tell me,” he said he wanted to know, “who took the pictures of you?”

Sometimes I tried to tell a different story. But he liked best when I told him about the man and the woman together — together with me. I learned that the more froideur in my tone, the more heated, the more insistent he would become — until I would be unable to continue because his mouth would be stopped up.

“Don’t let the game warden see you,” said the man painting the dock. “Indians the only ones allowed to net fish.”

The net I was sweeping through the shallow part of the lake was a child’s butterfly net I had found in the sand. The dock painter who warned me against the game warden was the same dock painter who had told me that a black racer was a water moccasin. I didn’t tell him I knew he was wrong, but let him think I was rash for reaching in after it.

People on the lake were ready with the rules, rebuked the fantasy daily. The vision had been: Swim with the dog, shoulder-to-shoulder, every morning, to the other side. But a hand-stenciled sign was posted when the season started: NO DOGS ON BATHING BEACH, though dogs were not the nonreaders leaving Band-Aids and cigarettes in the water.

The seven hundred dollars I had paid in dues covered plowing snow, but I would not be getting the benefit of winter. I had moved here for the lake, and then would not go in the lake; I’d be gone before leaves began to fall.

The former tenant said she had recovered here. From what, she did not say, but she said she had given herself five years to do it in. Well, was there anybody who wasn’t here to get over something, too?

His letter was forwarded to me here.

“I believe I need another look at someone who writes such a charming letter,” he said.

I had written to him after our meeting two years before. I had told him everything in that letter as though he had asked for me to. I had written him the whole time I was away, a woman he had met just once. And then he wrote me back. He invited me to see his new work. He had a show opening soon, he said, and the paintings were not, he said, anything like what he had done before.

He said he liked the way I described the place where I had been, where the small group of us lived, and got better. He said he liked the sound of the beach where we went when we were given a pass. He said he had tried to paint such a place, and maybe I would like to see it.

I had twenty years to go to get to be as old as he was, and then, if I got there, I’d have to go counting almost twenty years again. I was still in my thirties, but I was the one of us who was old. Anyway, he said he was nostalgic for my past.

I had a past, and my past contained a marriage and a job and friends. But I had long since dispensed with his past. I had spent the year before moving to the lake at a place where people recover from the bad things that seek them out. For the time I was there, I wrote to this man although, or because, I had met him only once, and because I felt our talk had been not an exchange of words, but of souls.

I read about a famous mystery writer who worked for one week in a department store. One day she saw a woman come and buy a doll. The mystery writer found out the woman’s name, and took a bus to New Jersey to see where the woman lived. That was all. Years later, she referred to this woman as the love of her life.

It is possible to imagine a person so entirely that the image resists attempts to dislodge it.

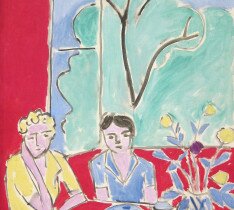

I lived in small rooms with heaps of bleached shells on distressed white tables and antique mantels. His place had the original brick arches between the large open areas of the loft. There were polished wood floors (slate in the kitchen and bath), and a frosted glass-and-steel screen hid the staircase to the upper bedroom. His paintings were hung in the enormous studio on the first floor, the range represented by portraits and landscapes following the early “systems” paintings. There were ordinary workday scenes supported by strict and intricate organization that a critic had commended as “art that conceals art.”

Lying in bed early on: “We had rules,” I reminded him. “I could fuck the wife anytime I wanted. I could fuck the husband if the wife was also present. The wife could, whenever she wanted, fuck either one of us — her choice: together or alone. The husband needed no rules, both we women felt, because, we also seemed to feel, we would have no idea where to start in the drawing up of them.

“They took me up,” I told him. “I was young,” I reminded him. As if he, of all we did, needed reminding!

“Which of you would make the first move?” he asked.

“The first time or any time?” I asked.

“Maybe the wife started it?” I said. “Maybe the first time she made a preemptive strike? Maybe she saw the way her husband was looking at me — I guess she made up her mind to beat him to it? You know, later on she told me that was exactly what she was doing.”

“Tell me what you had on,” he said, “the first time, and every time.”

“The wife said any dress looks good in a heap on the floor by the bed.”

He said he wanted me to tell him about myself and about the woman when the two of us were in bed before the husband came home, how we would not let him join us at first, but let him crouch beside the bed, his eyes at the level of our bodies on the mattress, first at the side of the bed, and then at the foot of the bed. And who had undressed first — had we undressed each other?

“Would you do anything — everything — they wanted?” he asked, although the real question was, Would I do everything with him?

Let him find out!

“It wasn’t always like that,” I said. “Sometimes we just let the cats sleep in the bed.”

“Oh?” he said. “Did they come into it in some way? There was cat hair in the sheets? On the two of you? On the three of you?”

“And did you like to be watched?” he prompted. “Did you like it more when she watched you with him, or when he watched you with her?”

“Don’t forget the neighbors,” I said. “The couple who watched at the window where the curtains didn’t close all the way. The man I didn’t mind, but I thought the woman wanted to take my place, and I felt she resented me for it.”

“You had never done anything like this before?” he said.

“I saw no reason not to.”

“It was the great experiment,” he said. “Did you wait until evening? Often you couldn’t wait.”

“That’s true,” I said. “I was supposed to be available.”

“Every day,” he said, “they touched you every day? Even on Sundays — you made yourself available to Saturday night’s predations?”

“All the better,” I said. “The better it was, the better it was.”

“You mean the more, the more of them?” he said.

“Repetition fueled us,” I said.

In the bed where I described the couplings years ago, he would suddenly roll me over so that I was on top. He would tell me to lean over and show him how my hair had made a tent over the face of the husband or of the wife.

It started up with us at the place we went for dinner after leaving his friend’s opening at a gallery in Chelsea. I had strained to say something kind, and he had pointed out the flaws in the artist’s logic; he criticized the concept as well as its execution, and was not wrong.

His voice, doing so was — sophisticated. It was a young man’s voice; it was dignified and persuasive, and made me feel like an accomplice. Under the words, his voice seemed to say “You and I are looking at this together, and we see the same thing.” When I could keep up with him, that was true.

We walked easily together; I leaned into him, my head almost to his shoulder.

He continued the analysis over dinner, and as we were finishing, he said, “What if one told every truth! Recorded the most evanescent reactions, every triviality, an unimpeded account of lovers’ minute-by-minute feelings about the other person: Why didn’t she order the braised beef the way I did? She raved about the sea bass, wrongly. I set my watch three minutes fast; she set it back.”

Here he took us into the future — he reached across the table to stroke my hair. “And I’d say, ‘What about her hair across the pillow? I had thought it would be finer.'”

His stance was not unlike the one I had proposed to him in my letter, that we observe the Wild West practice: We put our cards on the table.

We moved into what he called “the precincts of possibility,” of anything-goes, of nothing undisclosed.

He wanted to hear “cock” and “cunt,” but I was more likely to want to show him what the man and woman did to me all those years ago. He had told me to say we did it twelve times. Did what? What we did, well, wouldn’t that be up to me? Didn’t it have too. I told him what they did to me the first time, and the second, and the third through the eighth and ninth — some nights I teased him: “That’s it. I can’t remember the rest. Sorry. Only remember nine.”

But he was persistent, encouraged me to continue, to say more, to remember, to get it right. And when I really could not remember what happened the tenth time, I made something up. I made up something I guessed would be what he wanted. For example, he wanted to know when the husband was with both of us at once, whose name did he cry out when he came? He asked for the tenderest time, the most violent time, the most nonchalant time, the classiest time, the first time and the last time, all twelve times.

“And everyone was the better for it?” he said with admiration. “You were each made to feel more yourselves?”

“Of ourselves,” I said.

I was never more myself than when I was lying in this man’s arms. But was I ever much of myself in them?

“Don’t you ever get jealous?” I asked.

“Of course I do,” he said. “I admit to ineluctable jealousy — comparisons, comparisons, real and imagined. And, as it happens, there exists in me — not pathologically, but all too humanly, I think — a species of delight arising from this knowledge. Darling,” he said, conspiring, “are these conflicting sentiments and the mystery they point to not at the core of our alliance?”

I was never late.

By eight o’clock, he would already have ordered dinner for us. The sushi would be delivered in an hour, and left by the door. Some nights we did not make it past the entryway before dinner arrived. Some nights he would close the door and then press me against it, or against a wall, and hold me there until we dropped to the polished wood floor together — we would not have said anything to each other. And we would stay there until we heard the brush of the delivery man outside.

When we finished dinner, he would put on music for us, something he had looped to play over and over again, a piece he had chosen or something he knew I liked, something we both liked to hear behind us.

Then he would be inside me again so quickly I was, each time, surprised.

Kissing my eyes, he said, “Did Phillip start like this?”

And that night my husband would be Phillip.

The first time I went to see him at the loft, I found something he didn’t drink in the kitchen. I didn’t like it either, and on subsequent visits I checked to see if the level of juice in the bottle was lower, if the juice-drinker had been to see him. This changed the night I told him about the twelve times. He asked me to come back the next night, and the next. Each time I looked, I saw that the level of juice was the same. That is when the place became a sanctuary for me, and which of us does not need sanctuary all the time?

I tried to remember what I had told him the time before. That Katherine — I was calling the wife “Katherine” — took me home after taking me to lunch at a grimy place in China Basin, a fishermen’s supply shop that sold bait next to the coffee and doughnuts you could take out onto a dock and eat while oil tankers got overhauled. “Did she want you to undress? Or did she want to undress you herself?” he wanted to know. He was twisting my hair as he spoke. He could not braid it with only one hand, so he twirled it around his fingers and let it spring loose again.

“Show me how he kissed you,” he said.

I kissed him in a way I imagined Katherine might have done.

He said, “When you kiss me like that, my heart is so stolen.”

Not lewd, not urbane, not leering or concupiscent, but devotional. That is how I felt about Katherine and Phillip, and about the man I offered them up to. He looked for jolting carnality, for physical imperatives. “Didn’t more rules appear with a certain periodicity?” he wanted to know.

We were awake in the middle of the night, in the early morning, really. I had been lying still, rubbing a finger on the mended spot on the sheet where hydrogen peroxide had made a hole when he rubbed at a spot of blood — not mine. He got out of bed to turn off the air conditioner, and wrapped himself around me when he returned. With no need of a segue from my hurried-off clothes on the floor, I said, “I can’t remember — does the week in Acapulco count as one time?”

“I want each time in Acapulco,” he said, as I knew he would.

I gave him a familiar travelogue just to see how long until he’d interrupt with “Cut to the chase — the beach, the waves, sunset, dinner, you’re back in the house in bed.”

I pushed him off me so that he could come back even closer.

“We chose a room with a skylight above the bed. It was smaller than the other bedrooms in the rented house, but we wanted to see the stars. Phillip would not be joining us for another day or two, so the mood was hen party, sorority house.”

He moved steadily inside me, so wonderfully inside me as I spoke. When he asked me a question, he spoke into my mouth. I had to turn my head and tell him to repeat it in my ear.

He smoothed his hands down my silk camisole and asked me if I needed to be coaxed. “Did you reach for Katherine first?”

“Not then, maybe not ever,” I said. “It was not a lack of desire,” I told him. “I took an active part by setting desire in motion. To be in a condition of readiness is to participate fully,” I said. “As I am now.”

“Show me what she did to make you come that night,” he said.

In showing him, I took him to the other side of himself.

A short time later, he pulled me down to the thick carpet in front of the tall oval mirror. He put a pillow beneath my head, and another under my hips. He said, “When Phillip arrived, did the three of you spend that night in the room with the skylight?”

In fact, I remembered pleading exhaustion that night, and sleeping by myself downstairs. But there was nothing for him in that. I gave him instead a scene from a live act I watched through a one-way mirror in a South-of-Market theater. Phillip had taken me there on a night when prohibitions turned into permissions. Neither of us had told Katherine.

I dressed for him on the night that made it a month since I had started meeting him at the loft downtown where he waited for me “all pins-and-needle-y,” he said.

I had had to go to a dinner first, a benefit for something worth giving money to. The transition was too quick, the way it is when you fly to a place that you need train time to adjust to. On the way to the loft, I had felt tired by what went on there, by the bottomless pit of it, the ever-ratcheted-up attempts to hold his attention on me.

In the bedroom there was a movie playing. I recognized it as one of the red-boxed collection in his bedroom closet. We had watched this one before, the one in which the male star auditions Polish girls for his next film. Were they really in Poland in the film? Who could tell? What mattered was that these were the girls who would do anything, anywhere.

I arrived during the scene where the two girls, maybe nineteen years old, are lying naked beside each other in a hotel room. The star opens one girl’s legs, and then the other’s, for the camera. Both of the girls have shaved, or have been shaved. Then the star pulls the first girl, the blonde, into a sitting position on the edge of the bed and, standing in front of her, forces his cock into her mouth. It is possible that the scene is, to some extent, unacted — the size of his cock forces tears into the girl’s eyes.

When the actor is finished with her, he turns to the second girl, who has been watching him with the first. He turns her over so that he can fit himself into her from behind; at the same time, another man (he had been lounging in the chair earlier, naked) pulls her on top of him and enters her from the front. While this is going on, the first girl wipes her eyes and breathes with her mouth open as she watches the girl beside her on the bed. After a while, the second girl cries out in Polish.

“The thing about these films,” he said, “is that this really happened. We’re seeing something that actually really happened.”

I tried to rally to the feel of his hand on my leg. But a part of me was still at the dinner, greeting guests in black tie.

“You know why I want to see you with another lover?” he said, watching the screen. “I want to see a secret you — I would trade possession of you for it.”

He had offered to bring in women who modeled for him, and I had declined. I knew there was no one he would rather see me with than Katherine.

I thought of the photographs he had taken of me. He had felt the results were not worthy, did not resemble the nature of what was. He said, “They do not convey the trance you occupy during those times, the trance both of us inhabit, one with the other, one on account of the other, during those times.”

“So what is seen is not what is felt?” I asked.

He said, “No instrument carried from a prior place could be expected to capture the feelings effected there.”

I had already found the photographs he’d taken of others in a portfolio in another part of the loft.

The moment I wished he would turn off the movie, he muted the sound and turned his attention to me. This quality of attention righted things between us.

Then we were all flesh, and all feeling in that flesh. We abided in it, joined and rejoined, distance collapsed.

“Harmony,” he whispered.

I said the word back to him.

Harmony sought, harmony required. “No life lost to us,” he said.

“No one tells me better stories,” he assured me. I was aware of the point at which a compliment becomes a trap, because you are expected to keep doing the thing you are praised for; resentment will follow when you stop.

“Lie back,” I said.

That night I had worn my grandmother’s diamond earrings. I thought I might leave one behind in his bed the next morning. The moment this occurred to me, I thought, Why should he require an object to bring me to mind?

The music he had put on was a medieval motet. Two voices begin, and are joined by two more, then two more, until forty-eight singers are holding forth together. It has the hypnotic effect of a chant, but it is song. I knew that if he ever hard this music out in the world, I would be the person he would think of. There it was again, thinking in terms of souvenirs, what you take away from a place to help you call it back.

Obediently, he lay back in the barely lit room. I kept on a sea green slip and joined him, sitting on the bed so as to force his legs apart. I stroked him slowly and said, “The time in the pool at night? There was something I left out before.”

“This was in Laguna?” he said, as though he could have forgotten.

“Katherine and I drove down in a day. We left at dawn and took the Grapevine south — not much to see, but we wanted to make the best time. I wanted to watch the sunset from her sister’s pool. We only stopped at that place that has the oysters.”

“I know that place — ”

“That’s the one,” I said.

“Her sister lived in one of those heavily landscaped compounds where several bungalows share a large pool. Night-blooming jasmine was planted around this pool, so the air smelled good when you swam after dark.”

“You wear jasmine sometimes when you come to me,” he said.

“We both gave in to the drone of the drive, that line down the center of the state. It was driving with a destination, but with nothing required of us when we got there.”

“The way you can drive in California!” he said. “I used to love that about it.”

I reached for a bottle of almond-scented oil. I poured a little in my hand.

“We didn’t unpack at first,” I said. “We pulled on bathing suits from a duffel bag and wrapped beach towel sarongs around them. Except that I had been unable to find mine, and had packed a leotard instead, the Danskin kind with the narrow straps, flesh-colored.

“There were only two other people in the pool. Two men were doing laps in the deep end. Katherine and I stood in water up to our breasts and held on to the edge of the pool with our arms stretched out behind us. The water was heated, and it swayed against us slowly from the emotion of the swimmers doing laps.”

“Time was slowing way down,” he said, he eyes closed.

“We stayed like that,” I said, “until the men climbed out of the pool and lay down on chaises spread with towels at our end.

“Are you with me?” I asked.

“Darling,” he said.

“Katherine churned the water around her, and when she did a handstand, I saw that she had taken off her suit. The men saw, too, of course. They were quite a bit older than we were, and wore plaid swimming trunks. What an awful word — trunks.

“Are you listening?” I asked. “Because one of the things I just told you was a lie. Can you tell me what was the thing that I made up?”

“You mustn’t tease an old man.”

“But really,” I said, suddenly exhausted, “don’t you have something like this on video? Maybe we could just watch that?”

My voice was raw, and when I coughed, he got up to get me a glass of water. On his way back from the kitchen, he stopped to play back messages left by callers during the night.

He asked about the place on the lake but he never came to see it. He had done all the traveling he was ever going to do; that was the impression he gave. Now he traveled in time, taking me with him to where he had gone when he was a go-er. I was not so eager to go anywhere, really, so this didn’t bother me, except for once when I thought we should drive to Maine. I wanted us to drift in a canoe across a calm, cold lake, and listen to loons.

He had been to a lake in Maine with someone else years before. He said his Maine had been a week at a famous fishing camp whose pricey guides took your family out at dawn and then fried your catch for lunch. What occupied him now was seeing how far a person could go in the realization of pleasure, without leaving home, two people in a bed.

I had not heard from Katherine for many years when her forwarded letter reached me. She was coming to New York, and she said she wanted to see me. I did not think this was coincidence; I felt I had conjured her by talking about her every night. I was excited and panic-stricken. I wanted to show them off to each other, and that would be a disaster. The three weeks’ notice had shrunk to a couple of days. I left a message at her hotel to hold for arrival.

Last night I found him looking at Raphael’s Alba Madonna.

He held the book so I could see. “Why is she facing left instead of right?” he asked. “Why the triangular arrangement of figures? Why a river in the background? Why is she wearing red?”

“Because a human being made this?” I said.

“Because a human being made this,” he said, pleased.

The window shades were up. I looked across the way to a window that was covered in sheer white fabric. The room was lit behind it so the woman in the room threw a visible silhouette. She was posing, or maybe doing a kind of yoga. Then a man joined the woman and she turned out the light.

“This dress is very beautiful,” he said, his arms around me.

“An old gift from Katherine,” I said. The seamstress had done a good job on the vintage navy lace. I had asked her to give it a lighter look by removing the silk lining from the knees down.

“I want to hear about your friend,” he said, undoing the hooks and eyes. “But first I want to fuck you on this couch,” he said.

“You do give it a gentlemanly contour,” I said, by way of welcome.

“Are those tears?” he asked, smoothing hair back from my forehead.

“It’s better in French.”

“What is?” he said.

I told him part of a poem I was thinking about, one I’d had to learn in school in French as well as English: ” . . . From home and fear set free, . . . / . . . even the weariest river/Winds somewhere safe to the sea.”

“You’re going to meet Katherine,” I said.

“It’s brilliant,” he said, “liberating the past for a revival in the present.”

His questions about Phillip had been abandoned some time back, but he started up again about Katherine and me. He suggested I bring her with me next time I came to the loft. Well, of course he did. I said I thought we might do better in a gallery instead, with objects between us to look at, as we had. I knew he would be winning when I made the introductions. Katherine would be appreciative and intelligent and unimpeachably cordial to him. She might take a camera from her bag and take our picture, his and mine, then hand the camera to him to take one of her with me.

One kind of woman would phone him the next day. He would want to be helpful, and what would begin in passion and deceit would wind down to something ordinary. It would fill my mouth with stones. But maybe Katherine would do this, too? Would Katherine require his gaze?

“Tell me again — ”

Call-and-response.

Such an extravagant sense of what is normal. Depends on what you’re used to, I suppose.

All those questions, each of them a version of just the one thing: Was I better served in another’s embrace than in his own?

“We might clear a space,” I said. “You can’t fill every hour.”

“Is that what we’ve been doing?”

I never wanted to tell him.

He wanted his suspicion confirmed, although it would be ghastly to have it confirmed. I watched his salacity turn to fear. All the nights I had drawn out the exchange, holding back information, scornful of his boyish need to know, yet protective of that boyishness, too — his insatiable urging, wanting to savor of the way women are with each other, what they say to each other, him begging for female truth.

“May I count on you to utter the next sentence?” he would say.

I never wanted to tell him. I said, “I’ll show you what she did to me,” and he said, “But you can’t show me, I’m not a woman — you have to tell me.”

He was eager for the thing that would undo him. He had disallowed my earlier squeamishness, insisted I tear it apart. Okay. I would give him some female truth. What would have made me seem compliant when we started was an assault by the time I told him.

I told him in just one word.

I said, “The answer to your next question is: Precision. I can tincture it with more patently sexual language, but really, that’s what you’re after. Katherine was precise. I mean what you think I mean.”

He looked me over to see if I was playing.

A thrilling calm settled over me.

He propped himself up on an elbow.

“Look at that,” he said. “The single word that brings an inquisition to an end.”

I leaned back on the couch and let my breath out. I held his hand and thought, What now? Not asking him, but myself.

Because it was up to me!

I would not introduce him to Katherine; I would not give him the chance to tell me she was more beautiful than he had imagined. Let him reside in his failure of imagination; I had been generous. I had more. But it was mine. I led him from the couch back to the desecrated ground. I lay down next to him. I wanted to console him — I sent a herd of words and the dust rose and it was not enough. He had told me to say we did it twelve times. Well, maybe it was twelve times, and maybe it wasn’t any times at all.

You want the truth and you want the truth and when you get it you can’t take it and have to turn away. So is telling a person the truth a good or malignant act? Precision — that was easy. He had asked for it! There was more to tell; there would always be more to tell. If I chose to tell him.

In the meantime. I was never more myself than when I was lying in this man’s arms. We lay quietly, holding each other. Time was slown way down.

Finally he said, “Did you ever wear a linen dress on a summer day? A wheat-colored linen dress whose hem fluttered in a breeze? And did you pin up your hair on both sides so that your long hair funneled down your back in that breeze?”

I did not know who he was describing, but I said yes, I had dressed like that in summers when I was young.

“Darling,” he said.

I knew he was not entirely with me, and I had a shopworn thought: to be able to reverse the direction of time! But wouldn’t we have to go through the same things again in reverse?

“Darling,” he said again.

So here we go, careening along in the only direction there is to go in, our bodies braced for transport.

“Unimprovable,” he says.

From THE COLLECTED STORIES OF AMY HEMPEL by Amy Hempel. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., NY. This story was originally from THE DOG OF THE MARRIAGE © 2005 by Amy Hempel. Click here to buy: The Collected Stories of Amy Hempel