![]()

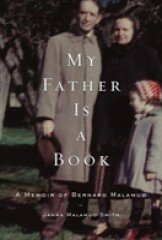

My grandfather, the novelist Bernard Malamud, died when I was four. I have no memories of him, but I was aware even in childhood that he was special, once counted with Philip Roth and Saul Bellow in what Bellow once joked was "the Hart, Schaffner and Marx of literature." Not until recently did I appreciate how lucky I was to have his legacy: seven novels and many short stories. As I began to work my way through his writings, my mother, Janna Malamud Smith, completed her third book, a memoir about him. Released earlier this month, My Father is a Book has, to my delight, received terrific reviews. I spoke with my mother about her father's influence on her life, and on our relationship. — Peter Malamud Smith

|

|

How did you start the massive task of writing this book?

The real question in starting a book is always, "What's the hook?" One was that people are interested in Dad, but the other was examining father-daughter love, or parental love. All my life, people who I didn't know would come up to me and say, "I knew your father — he really loved you." His love for me was such a touchstone in the way other people thought about him, and I just wondered what that meant when somebody loves you that much.

What surprised you when you were first going through those papers and letters?

I think the biggest surprise for me, and the most painful, was how central [his brother] Eugene's schizophrenia was to his life. And also to have my fear confirmed: that the trauma of his mother's illness and her suicide had been, almost, something from which he didn't recover. Even though I, on one level, had heard it and intuited it, looking at the papers was like looking at the corpse. He protected all of us from that.

Maybe for his own sanity.

He protected us in part as a way of protecting himself. He had witnessed people who had been victimized by the pogroms in Russia, and even though I grew up knowing what a pogrom was, I never had any idea about the intimacy of his own connection — that probably his stepmother had lost her family to those pogroms, that possibly he had lost his own grandfather. His biographer and I looked at each other and said, "His fiction is more autobiographical than we knew!"

And than he was ever willing to admit.

Oh, he totally wouldn't admit it. "It's just fiction, dear." It's a way of trying to get on top of the power that material has over you.

You said that he never recovered from his mother's suicide attempt when he was thirteen. I think in his fiction, the presence of women as damaging, starting with Harriet in The Natural, can be traced back to that.

That, and just that women tend in their writing to see men as damaging and men tend to see women as damaging, though maybe not completely. But I think you're right that the form it took with him probably came more out of his own trauma.

How do you think that feeling towards women related to his relationship with you, and to his idealization of you?

I think he partly idealized me to protect me from the part of him that was so devaluing of women. But I was sort of a conflict for him. He wasn't sure how to reconcile the part of him that wanted me to see the world as my oyster with the part of him that really wanted me to take care of him. He made a genuine struggle with feminism. He did try to appreciate it. His own needs, his own wish for nurture and care, probably made it harder. But I think intellectually, he got the hang of it.

|

|

Bernard Malamud

|

Did you have to fill the role of his mother?

To some degree, but it's more complicated than that. He wanted me to really idealize him, he wanted that little girl's love to go on forever.

Well, it's interesting in Dubin's Lives that Maud, the character who clearly reads as a stand-in for you, is so painfully independent.

But then they write a book together, so there is that sense of reconciliation, maybe.

There are so many examples through history of bad circumstances producing extraordinary ambition.

Right, and I think the one advantage of the extremity of his circumstances was that they forced him into that. There was no middle ground — what else would he do? And the other part of that is that you want to restitute, you want to be the avenger for your whole family's suffering, too.

You haven't said much about Arlene, his mistress. How did it feel to contact her and talk to her for this book?

It freaked me out a little bit. I didn't want to. It's something Ms. Manners doesn't cover: how do you write the letter to your dead father's mistress about wanting to print parts of her love letters? We needed a lot of back and forth because it just took a long time for her. And I feel empathy for her about this. This thing that happened forty years ago in your life is now going to go public, and you have no control over that. On the other hand, the letters were great and I really wanted to quote them. Some of it's fabulous.

Was it painful for you to read them?

It actually wasn't painful, other than what I said in the book. I felt some curiosity about it. I also found them sort of familiar. I mean, Dad was Dad. He liked to talk to people about what he was reading and what he was writing and what movies he saw. He wasn't a guy who put extensive intimacy on paper, so I wasn't reading through stuff that totally embarrassed me. Even his love letters are pretty succinct.

I think the book put words to what I perceived when I was little about who you were. Even though he died when I was very young, there was such an awareness of his presence. I'm wondering how you think he shaped your actions as my parent.

At one point I chastised you in his presence slightly and he corrected me. He didn't want me to. It was very sweet. I never wanted a room of my own when you were young. He was all about having a study of his own, and I would think very carefully about whether to go in there and interrupt him. One of the things I felt was that I never wanted a space like that in our house. There were parts of his specialness that, even though I haven't completely escaped it, I don't want to recreate overtly.

Most of the time we're looking for a mate, we're trying to find someone to fill the role of one of our parents. The people who I get involved with usually have characteristics that you have — a feistiness, an intellectual curiosity, the integrity and sense of humor. I wondered, given the intensity of your relationship with your dad, how you thought that affected your relationship with my dad.

I think there are two pieces to it. One is, it seems almost impossible, if I were to be brutally honest, for me to imagine marrying someone who doesn't know literature. Literature was a religion for Dad, and I think that it was for your dad in a way too. The other thing is that your father is a consummate teacher, and my father was a consummate teacher. I think that the fabulously important difference to me is that your father is so much less interested in dominating than my father was. Your father doesn't have a narcissistic bone in his body, and to be freed of all those narcissistic dilemmas in another person was such a gift.

Where I thought you might be going with the question, and what's sort of scary to me, is how hard it is to get away from the core values that you're raised with. Not that I've wanted to, but why haven't I wanted to? Why have I given so much value to literature, so much value to social justice . . .

Cause they're the best things! [laughs]

[Laughs] Exactly! Give me a child till he's seven and he's mine for life.

I wondered if the intervening years since Grandpa's death have allowed you any critical perspective on his legacy, and if you think he's due for a resurgence in popularity.

Absolutely overdue [laughs]. In writing the memoir, I finally had to read the stuff I hadn't read before, that I had avoided because it was just too close. I would say that my favorite Malamud is still his short stories, and The Assistant.

Since reading your book, I've felt so much gratitude to him, because he's what has allowed me to do what I wanted to do — to go to college, to write. Every day, when I get my bagel, I'm thinking that my great-grandfather would've been spreading the cream cheese, and I would be too if not for his talent and tenacity. But I also feel so grateful to you for the sense of kinship with him that you've offered me by writing it. The book is dedicated to me and [my brother] Zack, and I see it as a gift. Most people whose grandparents died when they were four don't get to know them in this way. And I feel the same way often in reading his novels and stories, that so much of the psychology and personality and sense of humor is so familiar to me, like a long-lost family member in some way.

He would have been such a friend to you, and you to him. He would have loved you. In a funny way I replicated what he did by not talking too much about him.

Of breaking from the past.

Right. But what's also so moving about what you're saying is how much we want the past back, don't we? And how important it is to us to get it. That was the other reason I wrote it. Because I wanted you and your brother to have what you hadn't had. n°

To buy My Father Is A Book, click here. |

©2006 Peter Malamud Smith and hooksexup.com.

Commentarium (1 Comment)

Loved reading this Peter