There are things we think of as separate: kid stuff and grown-up stuff. Sports and comedy. Love and sex, perhaps. The awe we feel when we see someone spin on a wire, and the awe we feel when somebody has an orgasm in front of us.

There are muscles that are hard to imagine using in a vaudeville routine, except maybe in Thailand.

There's a reason we call it a "sexual act."

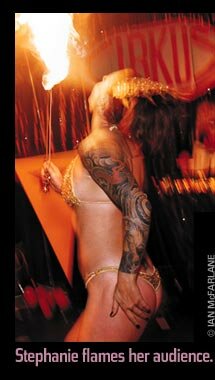

Stephanie strides onstage, her Heinz-bright hair up in a bouffant, the fringe on her thong swaying. Two business boys to the left of the stage giggle. "Check it out," mutters one, and they start up a running commentary. She's hot, they're thinking, all creamy skin and welcoming smile. Then their fever dream bends over, grabs two lean metal wands and some fuel. The boys go silent. Undulating her hips to the music, Stephanie begins eating flames as if they were drips of red syrup, dousing the fire with her lips and pulling it out relit, then making the silver wands dive and whirl. It's an act that alternates with each flicker from erotic to circus-sweet, toggling like a holograph.

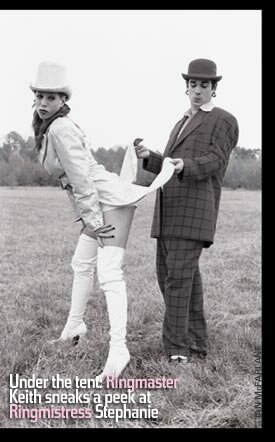

For six years, Stephanie Monseu has been performing with the Bindlestiff Family Cirkus, an alternative troupe she founded with her boyfriend, Keith Nelson, an anarchist-juggler with a tattoo of clown patriarch Emmett Kelly, Sr. on his left bicep. The circus mixes classic vaudeville acts with performances that go beyond the raunchiest burlesque: sword-swallowing side-by-side with its literal analogue, auto-fellation. Travelling in a Muppet Bandlike van studded with circus memorabilia,

they've performed everywhere from an Arkansas opera house to a Gainesville community center to a San Francisco queer bar. Over the years, Stephanie has extended her performance skills in some wild directions cracking a precision whip, walking on stilts, flexing her vaginal muscles for the notorious dildo-plate-spinning routine that (depending on the venue; it's illegal in some areas) closes the show.

they've performed everywhere from an Arkansas opera house to a Gainesville community center to a San Francisco queer bar. Over the years, Stephanie has extended her performance skills in some wild directions cracking a precision whip, walking on stilts, flexing her vaginal muscles for the notorious dildo-plate-spinning routine that (depending on the venue; it's illegal in some areas) closes the show.But her favorite performance remains flame-eating, the first circus skill she was taught when she was waitressing in New York. "When I learned how to eat fire," she says dreamily, as she packs up her stuff backstage, "Keith and I were in the alley at three a.m., out behind the restaurant where I worked, and the snow was coming down all around us. There's just something about taking fire into your body like that it's the primal fear, getting past those boundaries, the fear that it will get out of control . . . It was like a dream. Magic. Everything stood still."

It's not as if circuses aren't erotic already. Where else does an eight year old see adult bodies in candy-striped tights, spinning and contorting and sweating hard under hot lights? The whole ring is filled with people in drag. Then there's the sideshow; wander off and you're sure to find bodies, weird ones, ones you want simultaneously to look at and look away from. When a circus comes to town, even if your town is New York City, it triggers a special set of queasy fantasies: of itinerant carnies seducing locals in the sawdust, of muscled strong men and bearded ladies, of what such flexible people might be capable.

But a deliberately sexual circus is a whole other thing, a kid's pleasure with the gritty currents stirred to the surface. There's a thrill to it, but there's also something unsettling, as if you'd been flipping through The Cat In The Hat and he suddenly did what he always seemed to be threatening to do pulled out an enormous purple-and-red-striped schlong (whirling, beeping, shooting sparks, perhaps) and flopped it mightily onto the kitchen table. It's a shock to the system.

The Bindlestiffs are part of a tradition of '90s performance art that is, fairly or unfairly, associated with the cheaper strain of shock value: Lollapalooza, Jim Rose's Coney Island, alterna-strippers, drag, the whole modern primitive movement. But the troupe has its own jaunty flavor, made up of Wild West acts, Donny and

Marie, even Rip Torn's $1.98 Beauty Show, to which Stephanie merrily sings the theme song. While they may be explicitly influenced by some rather headache-y cultural studies theories about spectacle the notion that carnival tomfoolery can disrupt society's ideas of what normal really is they consider themselves primarily entertainers, reviving lost arts. Their role models are Abbie Hoffman and Emma Goldman, but also Carol Burnett. It's a bag of tricks that allows them to perform acts that in any other context would seem grossly pornographic, but that with the name "circus" attached, transform into a spangly parlor game something adults can be amazed rather than disgusted by. And there is a punkish trickster quality there as well, a feeling that you're going to get had, but you might like it. (Think Frank N. Furter slipping into bed with Brad and Janet.) When Keith remembers the first circus he ever saw, it's the scam he recalls: "It was the Mexican Tented Show, featuring the Elephant Dog! I thought it was the best thing in the whole wide world, getting money for a shaved dog." He laughs. "I was like, 'This is for me!'"

Marie, even Rip Torn's $1.98 Beauty Show, to which Stephanie merrily sings the theme song. While they may be explicitly influenced by some rather headache-y cultural studies theories about spectacle the notion that carnival tomfoolery can disrupt society's ideas of what normal really is they consider themselves primarily entertainers, reviving lost arts. Their role models are Abbie Hoffman and Emma Goldman, but also Carol Burnett. It's a bag of tricks that allows them to perform acts that in any other context would seem grossly pornographic, but that with the name "circus" attached, transform into a spangly parlor game something adults can be amazed rather than disgusted by. And there is a punkish trickster quality there as well, a feeling that you're going to get had, but you might like it. (Think Frank N. Furter slipping into bed with Brad and Janet.) When Keith remembers the first circus he ever saw, it's the scam he recalls: "It was the Mexican Tented Show, featuring the Elephant Dog! I thought it was the best thing in the whole wide world, getting money for a shaved dog." He laughs. "I was like, 'This is for me!'"Ten minutes before showtime, Keith stands in front of the mirror, prepping. First comes white powder, geisha-smooth; then black kohl. As we talk, he sketches in a classic tramp-clown: a moony, rueful Chaplin gaze. Then he pulls off his sloppy sweatshirt, revealing a pale belly and a Bindlestiff logo peeking out over his coccyx. Acrid fluorescent blue eye shadow; raw pink cheek streaks, like an '80s businesswoman after a bad makeover; lip sparkles; disco ball earrings. Purple fright wig like something rejected from drag Goodwill. Ribbed corset. He drops his brown corduroys and black briefs I catch a flash of something that looks like a piercing and on go fishnet stockings.

It's Kinkette the Klown and her Flying Disco Diablos. (A juggling act.)

Kinkette is just one transformation in a lifetime of quick-change acts. Keith has long been fascinated with clowns of all stripes. Mixing jester tradition with pervy drag is his specialty, but as he's gotten older, he's started to favor the sad-eyed "Weary Willy" travelling-tramp persona; it's closer to his personality. Tonight, though, he's performing a money gig at the Manhattan nightclub Shine, where, he shrugs, only the brightest colors can break through the fog of attitude. Thus, the garter belt.

Born in North Carolina, the child of high school teachers, Keith spent his early twenties travelling for radical causes. (He got an independent undergraduate degree in Anarchy at Hampshire College, the kind of place where that's not a punchline.) Now the revolutionary is in his thirties, in a steady relationship, but still on the road. If the circus is a cause, it's also a business. He worries out loud about money a lot, brooding on the subject of health insurance (an important perk when your employees hammer nails up their noses).

When he and Stephanie first met in New York in 1995, she was a former ski bum, hashing together a career in art school. His trickster intellectualism matched perfectly with her athletic showgirl vibe. But a life in the circus has pushed her skills to the limit, she says, making her think of her body in a new way, as something with strength inside and out.

The troupe doesn't only do raunch: they perform a cleaned-up version of the act for children's groups, and alter their performances to suit the venue. Still, they recognize that the sexual routines, the late-night shows, are what make them stand out. To Stephanie, these elements aren't titillating add-ons. "It's all about the power of the body, about the awe we feel at sexuality, its beauty," she argues. "These are muscles we never think about, that can do such thrilling things. In that way, there's no difference between an aerial act and a twat trick."

The troupe doesn't only do raunch: they perform a cleaned-up version of the act for children's groups, and alter their performances to suit the venue. Still, they recognize that the sexual routines, the late-night shows, are what make them stand out. To Stephanie, these elements aren't titillating add-ons. "It's all about the power of the body, about the awe we feel at sexuality, its beauty," she argues. "These are muscles we never think about, that can do such thrilling things. In that way, there's no difference between an aerial act and a twat trick."Some audiences take the implications literally: the couple has been invited to hang out in a lot of random hot tubs, and Stephanie is a magnet for couples looking for a third. ("I'm not interested in casual sex with my audience," she shrugs.)

Of course, that's not to say that everyone who sees them is turned on or thrilled by the sight of a naked contortionist or someone drinking their own pee. Audiences get grossed out, or angry; the troupe has had bottles thrown at them onstage. And then there are the cops. At a gig a few years back in tiny Slidell, Louisiana, Stephanie was interrupted midway through her introductory spiel for a troupe freak, The Horrible Bug-Eater. Stephanie was clad only in a top hat, a G-string, a jacket and a strap-on dildo wielding a black leather bullwhip when the door flew open and a bright light flooded the biker bar. It was the police, along with a film crew from a Cops-style local TV show. The Bindlestiffs froze; the cops froze; there was a long, freighted pause as they looked her up and down, taking in the silicone cock, and off to the side, a wild-eyed woman crunching a mouth full of crickets. "They just kind of turned tail and walked out," she laughs.

But a direct showdown is a rarity. The Bindlestiffs don't haggle with local venues. These are businesspeople too, they reason, and they don't want to cost anyone their liquor license because of nudity or illegal sex toys. Instead, Keith and Stephanie will announce to the audience why the local laws forbid them from performing their racier acts, a tactic guaranteed to get a crowd on their side.

Keith has toned down the anarchist jargon over the years, preferring to get the message across in subtler ways. "If you laugh, it's hard to be afraid of something," says Keith. "Like Scotty the Flaming Faggot he's just so sweet, so beautiful. It's utterly disarming." (A charismatic fairy in a blue bunny suit, Scotty gyrates, jingles finger-bells, strips, then submerges himself in red wine.) "There are states where if you just pull out a dildo, you've really pushed the envelope. Whereas in New York, you can walk into a place where a midget is fist-fucking somebody onstage, and in some places, that's the norm," he sighs. "Elsewhere, you don't have to cut off an arm or a penis to get applause." <> Still, each time they revisit a location, they try to push things up a notch. There's burlesque striptease aerialist Tanya Gagne. There's Magic Brian, who blindfolds his audience volunteer, then pulls out his cock and says, "What? What?" There's Buckaroo Bindlestiff's Wild West Gender- Bender Jamboree, plus all manner of juggling, tightrope walking, piercing, rowdy music and the bed of nails.

But the lucky towns, the ones that get the whole deal, the ones that can go all the way they get the plate-spinning act.

It's the Bindlestiff trademark. It's what people make fun of when they want to make fun of them, and what they giggle about when they're thrilled.

Sometimes the troupe itself goes back and forth on whether to do it "It's on!" "It's off!" If the audience is wrong (drunken frat boys), Stephanie will give a thumbs down.

The routine doesn't look like Keith's initial brainstorm: "I had this image of nine asses, with sticks poking out of them," he recalls. Egalitarian, but he couldn't find nine willing asses. Perhaps it's for the best. As odd as it sounds, the act is elegant. Keith and Stephanie walk onstage, looking like nothing more than a courtly vaudeville couple: Stephanie wears a strapless black silk '50s cocktail dress, very Lucille Ball. Tinkly music plays. She hands him the white china plates one at a time, and he places them on the five background sticks, spinning the plates, in classic (or semi-classic) Ed Sullivan Show fashion, rippling the white china with his fingertips and the flats of his palm.

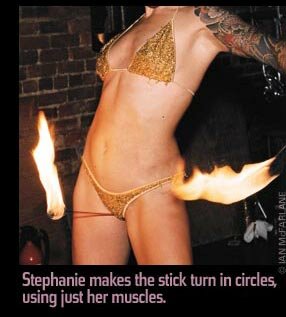

Then his lovely assistant drops to the ground, and in one graceful move, tilts onto her back and upends, so that her pumps float in the air. Her skirt falls back over her torso, revealing pale showgirl gams, spread wide, and her ass; her face is hidden. Keith takes a dildo, pulls on a condom, lubes it up, twists it inside her, and then places a spin-stick inside that. It's a little sick-making, this private thing in public. And then Stephanie begins to make the stick turn in circles gently, using just the muscles inside her. When Keith places the plate atop the stick, it spins like the others.

As the audience roars, Keith runs back and forth, keeping things going, the plates glimmering like tiddlywinks: sexual, not sexual, sexual, not sexual. It's uncomfortable and harmonious at once, and like most things you've never seen before, it gives you weird ideas. For one: What if sex was more like this? An act. One person spinning another with such tender frenetic attention to velocity, to balance. The loving teamwork of two show-offs. Two athletes. Two clowns.

"I do all the work," Keith shrugs. "She gets all the applause."