Frank Stanford’s life elicits a certain kind of fabled worship. Orphaned in Richton, Mississippi in 1948, Stanford was raised on the levee camps outside of Memphis, and later educated by Benedictine monks in Subiaco, Arkansas. He was married twice, but had countless affairs, some with well-known poets, writers, artists, and musicians. He was charismatic, funny, uncommonly handsome. And the lynchpin of any heroic artist myth—he died young, by three self-inflicted gunshot wounds to the heart when he was just shy of his thirtieth birthday.

If his contentious biography prompts a certain curiosity, his poems truly inspire a cult fascination. Due to the relative scarcity of his books, Stanford remains a sort of ecstatic secret amongst poets, spread by word of mouth. With the publication of What About This, the first unified volume of his work that includes hundreds of previously unpublished poems, his acclaim will, hopefully, surpass the cult status that’s contained him within his small but ravenous following.

You can always tell when you meet a Frank Stanford fan. Probably because, after about two whiskey drinks, a Frank Stanford fan will talk to you for hours about nothing but Frank Stanford. Where they first heard of him, their favorite apocryphal Stanford anecdotes, speculations on the women and men he might have loved. Most likely they’ll even quote you a poem or two, or seven.

I should know. I’m one of them.

♦

I first read Stanford’s “The Blood Brothers” from his first poetry book, The Singing Knives. Here, you meet the band of misfit characters that roam through so much of his poetry: a nightmare landscape of wonders, the Deep South gone epic. The world Stanford conjures is both mythic and utterly real, a dream of dirt and stars and blood, of murderers and blues singers, one-handed mystics and knife-throwing drunks, of lovers in the darkness, plotting their revenge. He supposedly wrote the damn thing when he was all of sixteen-years-old.

I was twenty-four at the time, living on P.S. Dean’s couch in Oxford, Mississippi. A state with much to be ashamed about, Mississippi has never had a problem with its writers. You know the list: William Faulkner, Eudora Welty, Richard Wright, Tennessee Williams, Barry Hannah, Richard Ford, Jesmyn Ward, Lewis Nordan, Natasha Tretheway, Walker Percy, and so many others, not to mention the countless blues, soul, and country musicians.

But Stanford, him I didn’t know. Dean, a fellow poet and friend, had left a flimsy paperback copy of The Singing Knives on the living room coffee table, right next to the couch I was sleeping on. So I read it. And I read it again. I got so excited I ran a lap around the house.When Dean came back from class we sat around drinking, reading the poems out loud to each other, passing the book and a bottle back and forth, all night.

The more we learned, the more Dean and I wanted to know. There wasn’t just one story about Frank Stanford, there were hundreds. He knew Allen Ginsberg. Lucinda Williams wrote a song about him. He popped up in Ellen Gilchrist stories. He started a poetry press with C.D. Wright, his lover. He was an “outstanding” martial artist.

Dean went to the bookstore and came back with the only other books in print: the slim and murderous volumes You, The Light the Dead See, and the gargantuan epic The Battlefield Where The Moon Says I Love You. A friend had warned us about The Battlefield. “It’s best to read it one time, straight through,” he had said. “Start in the morning with coffee, switch over to beer for lunch, and that night, when you finish it, you’ll be drinking whiskey.” That’s exactly what I did. I read an entire lifetime, fully immersed in a nightmare epic of childhood and murder, part fantasy, part biography, part prophecy. I was swallowed whole. Inside the poem you find Stanford the list-maker, the juvenile delinquent, the criminal drunk, the singer, the soldier, the samurai warrior. You get Christ and His apostles reimagined as riverside drunks. At 15,283 mostly unpunctuated lines over 383 pages, The Battlefield is an impossible poem, one to be lived in, not so much a river to swim in as an entire ocean to sail. I love it deeply, every perfect line and badly botched one, every scar and star of it.

♦

© 1973 Ginny Stanford

“All of this is magic against death”

—The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You

Franz Wright once called Stanford “one of the great voices of death.” Death isn’t just in the margins of Frank’s poems, it’s often a major protagonist. Take this section of “Death and the Arkansas River,” where Stanford presents Death as a sort of Deep South mob boss:

In the winter Death runs snow tires on his truck, He makes long hauls at night. Death pays the best wage, He can keep in touch on his two-way, He’s paid all the Laws off.

Death can afford whatever he wants.

Stanford was a death poet, true, but he was also a dream poet. Dreams are not just a passing fugue state in his poetry. Instead, they reveal, like orphan Stanford dreaming his “father was wading the river of death/With his heart in his hands.” But dreams are also reality; they bleed, they kill. “I dreamed a knife like a song you can’t whistle.” The Singing Knives alone includes at least 31 separate dreams. That is, of course, if they aren’t all the same dream, or if the poem itself isn’t some other dream altogether.

More than anything, like Basho, like Li Po, like Emily Dickinson and Yeats, Stanford was a poet of the moon. The moon cycles through nearly every of his poems. And it’s never the same moon sliver. The moon gravitates as a “beautiful white spider,” “a dead man floating down the river,” “a woman in a red dress/standing on the beach.” It’s “a plate with no supper,” “a clock with twelve numbers”, it’s “swollen up/like a mosquito’s belly,” it’s “the way you parted your hair.” More than a muse, or just some watchful deity, Stanford’s moon seems situated at the center of his universe.

It’s like he took that old Basho line to heart: “For a person who has the spirit, everything he sees becomes a flower, and everything he imagines turns into a moon.”

♦

Not all of our writer friends loved Stanford the way Dean and I did. I remember one cantankerous buddy from Kentucky, a novelist, remark about Stanford: “He would have been great, if only he’d ever learned how to revise.”

There is a case to be made for this. Some of Stanford’s poems carry a reckless quality that can come across as dashed-off, maybe even too raw. And let’s face it, when Frank blows a line, it can be painful. Still, every misspelling and botched line, every raw scrape unpolished on the page, revealed his mortality, his humanity, the very humanity he ultimately pronounced with three pulls of a trigger.

♦

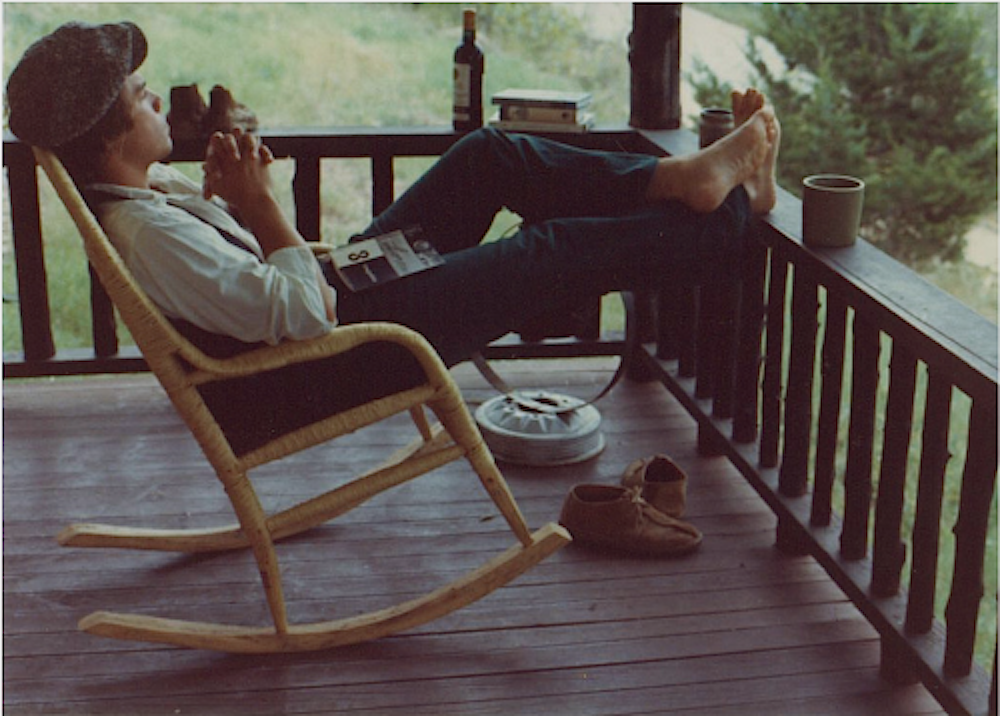

In the following years, Dean and I tracked down friends of Stanford’s, old teachers, ex-lovers. We searched for the Emery Home for Unwed Mothers where Stanford was born, but it had burned down in 1964. We met other Stanford fanatics, people who could point us to old acquaintances with a story to share. Some gladly talked to us, though most requested the conversations remain off record. We wanted to know what he was like, what it had been like to be in the room with him, to drink with him, to be him. What could it be like to have such a remarkable mind, such a wild spirit, to have a heart full of so many worlds? For every improbable story (Frank running into a lightning storm with a metal coat hanger, demanding God to prove Himself, or Frank dancing through a restaurant in a top hat and tails) we found someone else he had hurt, someone he had jilted, another string of broken hearts. People had loved him, been hurt by him, yet few people seemed able to intimate him. The title of the collection Constant Stranger seemed to grow more and more appropriate. He was everywhere, and always at arm’s length, unknowable.

Even though we were both only five years from when Stanford died, there was still time for us. It was as if by studying him so closely, by talking to people he knew, by just being close to his world, Dean and I would somehow conjure his essence, his spirit would impart some impossible talent on us while we slept, same as the Holy Spirit did for Cædmon, and we would wake up one day as the greatest poets that Mississippi had ever known. But after awhile of asking, Dean and I began to drift away from Frank, the person. In all our legend-hounding, we had encroached on something too painful. The wreckage of hearts, the discord, the time lost, the particular ghastliness of his suicide…none of that was ours. It belonged to his friends, to his family, to his lovers. However, what was left to us—the people who didn’t know him, who never would—was his art: nine books of poetry, one collection of short stories, and a film that I still hope one day to see.

We have the work, and the work is bounty enough. Sitting here, holding my copy of What About This, I’m grateful. All that magic gathered and bound for us, a spell book, a grimoire to remember him by. Magic against death.