|

|

Send to a Friend | |||

| Printer Friendly Format | ||||

|

|

Leave Feedback | |||

|

|

Read Feedback | |||

|

|

Hooksexup RSS | |||

![]() lan Moore's Watchmen remains the only comic book that resides on Time magazine's list of the hundred best novels of all time. A fractured, neurotic character study set against the backdrop of the Cold War, it brought a new depth to comic book heroes in 1987 by portraying them as real people, insecure and dysfunctional. Moore had achieved this in his work on DC Comics' Swamp Thing, Batman and Superman as well. In each case, he helped elevate comics from mindless summer reads to explorations of the human psyche.

lan Moore's Watchmen remains the only comic book that resides on Time magazine's list of the hundred best novels of all time. A fractured, neurotic character study set against the backdrop of the Cold War, it brought a new depth to comic book heroes in 1987 by portraying them as real people, insecure and dysfunctional. Moore had achieved this in his work on DC Comics' Swamp Thing, Batman and Superman as well. In each case, he helped elevate comics from mindless summer reads to explorations of the human psyche.

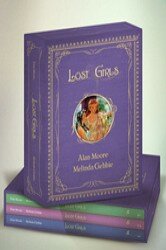

Now fifty-three, Moore's latest work, a 336-page epic fifteen years in the making, will be released next month. Lost Girls, created by Moore and his partner Melinda Gebbie, repurposes fairy tale icons Alice, Wendy and Dorothy as metaphors for sexual awakening and pornography (Moore's words). Grown versions of the three characters converge at an Austrian hotel and engage in an endless variety of sex acts as World War I closes in around them. It's an affecting parable about the importance of fantasy and the consequences of stifling sexual imagination.

Hooksexup spoke by phone to Moore and Gebbie at their home in London about the culmination of a decade and a half of work, and the controversy it's guaranteed to spark. — Gwynne Watkins

|

How did you create sex lives for the characters of Alice, Wendy and Dorothy?

We worked from the assumption that their stories were a fantastic elaboration upon events that might have actually happened. Wendy seems to be from a middle-class background, and there's something very feral and savage and lower class about Peter Pan and the Lost Boys. Then we started to think about how the various incidents in Peter Pan could be mapped onto this story we were developing. Obviously, Captain Hook is a very predatory presence, so to make him a sexual predator wasn't a huge leap. You've got his bete noire being the crocodile that swallowed an alarm clock, and he's trying to vicariously turn back his own sexual and physical clock by turning his attention toward children. And also, the crocodile is gaping jaws from beneath, a kind of vagina dentata idea.

That was one of the scariest images in the book for me, that huge crocodile vagina.

Along with its companion piece, the Jabberwocky from the Alice narrative. They're two of the most startling images in the book. They're also two of the funniest, because they explode those ridiculous fears that each gender has about the other at their most extreme state.

Was it clear to you from the beginning that you wanted the story to be about those three characters?

One of my initial ideas was simply noticing that Sigmund Freud suggested that dreams of flying were, in fact, dreams of sexual expression. Connecting that with the flying themes in Peter Pan sparked the notion that it might be possible to come up with a sexually decoded version of the Peter Pan story. But once I'd got that far, I seized up again, because I couldn't see a way that could be done that wouldn't simply be a smutty satire based upon Peter Pan, which, ever since people first noticed that Tinkerbell was kind of sexy-looking, there have a been a plethora of.

At this point, I'd met Melinda a couple of times. I'd been an admirer of her work since the Californian underground comics scene when she was with people like Crumb and S. Clay Wilson. We had a couple of preliminary meetings and traded ideas. At some point, I raised this vague, half-assed Peter Pan idea, at which point Melinda said she'd always enjoyed doing stories that revolved around a dynamic of three women. We projected a timeline in which Alice would be the oldest of the three, since her book was published first. She would be around sixty, Wendy would be in her thirties and Dorothy would be a twenty-year-old, just arrived from Kansas, which was good from our point of view, because one of the things that we didn't like about pornography was that it seemed to be one particular body type and one particular age.

|

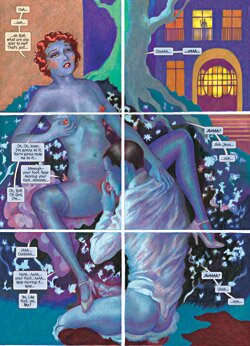

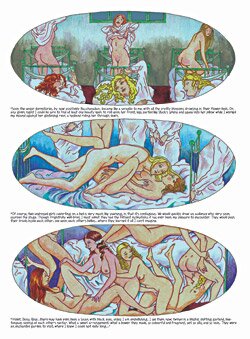

| Images from Lost Girls (click to enlarge) |

I assume you looked at many different kinds of porn in order to write this.

When I say I looked at different sorts of porn, I'm not sure that's accurate, because the majority of pornography is visual and photographic, or cinematic. And I'm simply not interested in that form of pornography, because the fact that these are real people means there's a lot of possible human unhappiness that is connected with all of those images, which to me is not really very sexual.

One of the reasons we chose the term "pornography" is because it's very specific. It is writings or drawings of wantons. It's keeping purely in the realm of the imagination. I found that a lot of the Victorian and Edwardian pornography was very good, surprisingly good, surprisingly liberal and surprisingly progressive. It was a kind of pornotopia. I did read some of the more modern stuff and I found that appealed to me less. My late friend Kathy Acker, who'd got a wonderful collection of pornographic books, I remember her lending me some of her favorites, and they were good-spirited books. But we found that, perhaps that sort of bondage, Sadian approach to sexuality has probably been done to death.

I find it kind of boring.

Yeah, that's it. It's boring. I mean, you can't write a work of pornography without, in some way, referencing the Marquis de Sade. He was simply too important to the genre. That said, most of his actual writing is incredibly boorish. I mean, even he, I don't think, got past the thirty-fifth day of Sodom before it all became too repetitive and dreary for him.

There have been rumors that Borders bookstore chain won't carry Lost Girls. Why does a comic seem more dangerous to people than a pornographic novel?

I don't know quite why that should be, because if you look in any sort of traditional bookstore, you will find literary pornography, a lot of it considered to be great works of art. And if you look in the art section of the same bookstores, I'd be very surprised if you couldn't find some of those bulky Taschen collections of great erotic art. So it's not really that there's any problem with the words. It's not really that there's any problem with the pictures. But it remains to be seen whether there's any problem with the combination of those two things.

You've said that you hope that Lost Girls will "break the genre open." What would be your ideal reaction?

I hope that Lost Girls would establish that it's possible to create works of art and literature about sexuality and the sexual imagination that were every bit as well-conceived and well-executed as any piece of art that exists in the world. There's no reason why pornography shouldn't have the same of standards applied to it as every other art form has. Since we are certainly going to have pornography until the end of time, or until the end of humanity, I would hope that there was a chance that there might be good pornography. However, Melinda and I, with no false modesty, we're both quite good at what we do. It has taken us fifteen or sixteen years to create Lost Girls. I don't think we're going to see anything like Lost Girls for a long, long time.

Did creating the parts of the book that describe incest or children in sexual situations ever make you uncomfortable?

It was certainly something we had to think about very carefully. What we decided was that it wasn't just important to make this a work of art and literature. It also had to be a genuine piece of pornography. Falling back upon Freud — as I'm kind of loathe to do, because I've not got a great deal of respect for his theories, but there don't seem to be any more persuasive theories to replace his somewhat dodgy ideas — but Freud is the paradigm that most of our thinking about sexuality is based upon, and Freud says that all sex is sublimated incest, which I don't believe for a moment. But Freud said it, you know? And looking at the Victorian pornography that I read, it is one of the things that seems to run through an awful lot of that.

Which was pre-Freud.

Which was pre-Freud. And so it seems that this is something that is very prevalent in the human psyche, and it would have been cheating for us to ignore with Lost Girls. Now, obviously it's a very prickly issue in contemporary society. But it's also one that's approached with staggering hypocrisy. The same newspapers that decry the comedian Chris Morris for doing a very funny satire of the pedophile hysteria will do, a little bit further down, a column talking about the developing bust of then-fifteen-year-old singer Charlotte Church, under the headline, "Charlotte's Chest Swell With Us."

Why set Lost Girls during World War I?

We are trying to present sex and war as alternatives to one another. The pornography in Lost Girls is a testament to the human imagination, and particularly to the human sexual imagination, and the war that builds ominously throughout Lost Girls is the exact opposite of the human sexual imagination. I perceive war as the ultimate failure of the imagination. When we can't think of anything else to do, then we kill each other in staggering numbers.

The ending of Lost Girls is very upsetting.

Thank you.

Is that meant to be a warning?

It's what the book's about. Take the character Rolf, who is a perfectly genial bisexual shoe fetishist throughout the first two or three parts. It's only in the final book that he's called up for duty, and we see him putting his boots on with exactly the same loving attention as he'd previously been expressing in his sexuality. It's as if his basic drives have been channeled into something which is not about pleasure, it's about going to the front and either killing people or getting killed or both.

Sex scenes have always been really important in your work. Part of me wonders how you got away with that.

Part of me wonders how I got away with it as well. I think you can get away with anything if you are pure of intent. Yeah, there are an awful lot of sexual scenes in my early work, and some of them very blunt. I mean, nothing quite like the intensity of Lost Girls. But at the same time, Lost Girls is a self-avowed pornographic book, whereas those earlier works were [laughs] supposed to be comics for fifteen-year-old boys.

Did you ever try to put sex scenes in the mainstream comics you wrote?

No, because with some of them, it clearly wouldn't have been appropriate. There's no point in putting a sex scene into Superman. It's too snickery. It's too sort of, "Oh look, here's a popular mainstream character having sex." It's schoolboy humor. Whereas the idea of Swamp Thing having sex with anything was such a strange one, and it struck me that you could probably sidestep all of the problems that people usually have about two human beings involved in a relationship, and you could probably do that with poetry and weird psychedelic imagery.

Another thing that comes up in a lot of those sex scenes is a theme of older men who are drawn kind of disgustingly having sex with younger, attractive women.

Well, other than Promethea . . . Um, well, I suppose, I suppose Swamp Thing, yes, I suppose he is an older man and he is drawn kind of disgustingly. I mean, he's got potatoes growing out of him.

And Mina and Allan Quatermain in League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

I think it's probably more to do with the mechanics of the stories, rather than any decadent agenda upon my part. But I'll let the readers be the judge of that.

One more thing. I was reading an essay on you by your daughter, Leah, in which she says that she had been your pubic-hair-continuity advisor on this project?

Yes, she was pubic-hair-continuity advisor to Melinda. When you draw a lot of panels, it's easy to forget the odd bit of pubic hair here or there. But, yeah, absolutely true. Credit where credit's due. As her father, I'm just glad that she's found a worthwhile occupation in life.

[Hands phone to Melinda]

God, the phone's hot. Alan's been doing some heavy breathing.

|

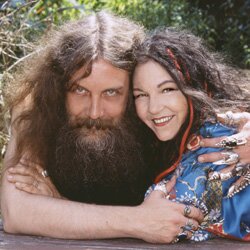

| Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie |

So, something I didn't get a chance to ask Alan: You worked on this for a long stretch of time, during which pornography became much more accessible because of the internet. Did that change the way you worked?

I think I've accessed the internet twice. I have absolutely no knowledge of how the internet affects people, except that they don't do shopping in the stores as much as they used to.

How did you start out imagining these characters as sexual? Was that a difficult mindset to get into?

Not at all, because I approached it purely from an absolutely personal point of view. When I was little, I thought there must be a book somewhere about sex that's attractive and interesting and beautiful and makes sense of everything. And for a while, I thought, well, I guess I have to grow up, and then when I'm old enough to look for a book like this in a library, it will be there. And there wasn't any book like that. It was just the nice photographs of women in Playboy magazine. And when Robert Crumb told me about having gone to the Playboy Mansion — he loves women, but he didn't like the Playboy Mansion. He thought the whole thing was frighteningly plastic and that there was no personhood and nothing spontaneous going on. It might as well have been a kind of Hitler Youth camp with tits.

The story of Lost Girls is very much about female sexuality, yet Alan is the one who wrote the text. Were there ever moments where you had to help shape the idea of how these women saw their sex lives?

There was almost never any discussion about language or description, but Alan did a lot of thumbnail sketches for me, and I would take the images he'd given me and say, well, look, I'm going to focus on what's going on in their minds, whether they look a bit wary or vulnerable or surprised or hungry or fascinated or whatever. And the hands as well. Women pay a lot of attention to the way other people use their hands, and women pay a lot of attention to body language. Even the slightest things: a slight move of the shoulder, a shift in the torso, the way the legs are positioned — all the self-protective shapes women make with their bodies. And then, as they relax, the more open gestures, the more relaxed features, the flush in their coloring. These are ways of reassuring the reader that they are safe, that the characters, for the most part, are in a supportive setting.

The first thing I said when Alan asked me how I liked the book is that I was very wary of it, because I felt a personal connection to these characters and I was scared they were going to be put into situations I would be uncomfortable with. But just the opposite happened. I felt the characters were very true to the stories, and that the women were very in control of who they were at all times.

We both worked very hard on that, and we had a lot of discussions before anything got written or drawn about how we wanted them to appear. We didn't want them to be people who were going to be imperiled once they were vulnerable. I think there's been a lot of damage done to the feminine psyche with the idea that not only does rape of some kind need to occur in a lot of pornography, but that it's assumed that's what the reader wants to see, and it's assumed that a woman can be brought down by an experience like that.

How does working on something like this for such a long period of time affect your relationship?

It's a major event for the two of us to have gone through, and it's a very peculiar project. But I think we've got a more solid understanding of each other.

Now that this is over, does it feel like you've lost something, not working on it anymore?

Oh, no. It was really, really hard. I mean, it was brilliant, and I learned so much, but I was glad when I finally put the last crayon down. And it was exhausting, because it just required the absolute best of us. And that's a good thing. n°

To buy Lost Girls , click here. |

©2006 Gwynne Watkins and hooksexup.com.

Commentarium (1 Comment)

This book just knocked me out. Brought me to places I didn't realize I'd forgotten.

Why is this interview called "The Brothers Freud"? Is that a Grimm reference?

Now you say something