|

|

Send to a Friend | |||

| Printer Friendly Format | ||||

|

|

Leave Feedback | |||

|

|

Read Feedback | |||

|

|

Hooksexup RSS | |||

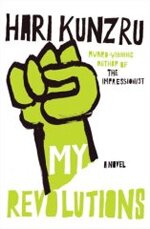

![]() oung writers are often warned about the perils of peaking too early, usually by older writers who haven't peaked at all. But Hari Kunzru, who, at age thirty-one, was paid nearly $2.5 million (in today's dollars and exchange rate) by an American publishing house for his first novel, The Impressionist, hasn't fulfilled his role as the wunderkind flame-out. Instead, he followed the success of his first novel with a second, Transmissions, about an Indian programmer working in the U.S. who releases a computer virus modeled after a young Bollywood film star. His most recent work, My Revolutions, deserves commercial and critical success as well. A taut, dizzying story of a Weather Underground-style '60s activist group, it reads as part potboiler, part existential muse on the meaning of protest.

oung writers are often warned about the perils of peaking too early, usually by older writers who haven't peaked at all. But Hari Kunzru, who, at age thirty-one, was paid nearly $2.5 million (in today's dollars and exchange rate) by an American publishing house for his first novel, The Impressionist, hasn't fulfilled his role as the wunderkind flame-out. Instead, he followed the success of his first novel with a second, Transmissions, about an Indian programmer working in the U.S. who releases a computer virus modeled after a young Bollywood film star. His most recent work, My Revolutions, deserves commercial and critical success as well. A taut, dizzying story of a Weather Underground-style '60s activist group, it reads as part potboiler, part existential muse on the meaning of protest.

|

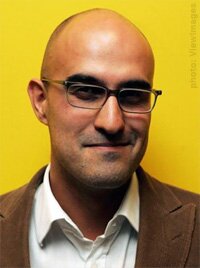

Despite his superstardom in the U.K., Kunzru (who is half British, half Indian) is far lesser known in America, which is baffling — his novels are the kind of thing Paul Greengrass lives to adapt. But with an unpopular war simmering and an economy that continues to shape-shift unsettlingly, Kunzru's themes of rebellion — from dramatic and violent, to personal and intimate — are more relevant than ever. He spoke to Hooksexup about the changing nature of protest, the mixed blessing of a giant advance, and where he told London's right-wing Mail on Sunday they could stick it. — Will Doig

Both of these books are about people rebelling against a system, but the character in Transmissions works within the system he's rebelling against, whereas the characters in My Revolutions are very much outside it. Do you think today people are more apt to try to change the system from within?

I think the big difference is our feelings about what things might look like. One of the notable things about the '60s is the ease with which people imagined they were going to overturn the vested power interest. Back then, people thought they had a clear picture of what another world — another way of social organization and economic organization — might be. We're now very skeptical that's possible. That sort of complete refusal of things as they are is quite difficult to make at the moment.

The two books also provide a good juxtaposition for showing how technology has changed the nature of protest. Today, one person who hacks into the Starbucks computer system and disrupts their operations is likely to get more attention than half a million people marching against the war.

Yes, protest now is incredibly powerful if it generates media. The street protests were quite effective during Vietnam, but however many million people went marching onto the streets to protest the Iraq war, it had no noticeable effects.

Why is that? Those marches were covered by the media. Were they just crowded out by all the other things in the news cycle?

I think there's more of a disconnect between the popular will and the elite who actually run things these days. Certainly here in the U.K., it was almost a revelation that the government didn't have to pay attention to us — there could have been two million people on the streets, and Blair could basically say, "Well, I feel your pain, but I have a lot more information than you do, and this is the right thing to do." There's now an acceptance that they are the professionals, they're our managers. And we're on the ground floor, and sure, we can talk about it by the water cooler, but that's all those protests were: one big bitching session. Then everyone went back to their desks and did their work.

I think we're also living in a very self-conscious age, which is why we couch a lot of our political discourse in comedy now: The Daily Show and Colbert Report, Real Time With Bill Maher, etc. It's like that comedy filter keeps us from worrying about looking foolish in front of our peers, because it's all just a semi-joke.

Yeah, I think we live in a very mediated time. For every possible opinion we could express, there are an endless number of precedents. You express something from the heart, and then you feel like you're expressing it in the manner of the last person you saw expressing it, or the guy on TV; it feels oddly second-hand. And putting yourself at social risk is discouraged, and policed by other people. And the heat gets turned up and up and up the more directly you try to oppose. People call you names, or call you "utopian."

|

| Hari Kunzru |

Let's talk about you personally. It seems like every news story written about you starts with the fact that for your first book, you received the largest advance of any first-time novelist in publishing history. It's already the first line of your obituary, as they say.

Yeah, that's greatly exaggerated. I was better paid than I ever expected to be, that's certainly true, but the true statistic was actually much more highly qualified — I was paid more for a foreign literary novel in the States than anyone else. If you think about the kind of money the big thriller writers get, Dan Brown or whoever else, it's just simply not true. It became one of those "internet truths." I became the Puff Daddy of novels.

You also turned down a book prize, which caused even more of a media ruckus.

It was a prize sponsored by The Mail on Sunday, which is the voice of what we call Middle England, very anti-immigrant, anti-gay, etc. They have this tone of total righteousness: hang 'em, flog 'em, send 'em back where they came from. I thought, I'm not sure I want to give them the cultural validation. They'd been running lots of pictures of asylum seekers trying to sneak into the Channel Tunnel, implying there was this tide of foreigners washing up against the gates of the Island of Britain. I was in India at the time, so I gave my agent something to read out, and he read the rejection, which said if they wanted to give the money away they should give it to this refugee charity, which they duly did, and they became the largest donor to that charity that year. It caused much more of a fuss than I imagined possible.

And you are biracial, which was stigmatized long after people began to accept racial minorities as equals. Yet in very recent years, at least in a place like New York, being biracial has almost become trendy, if that's possible. Have you noticed that in London?

It's extremely interesting. When I was a kid, it was definitely a problem because you didn't fit securely into anybody's gang. I grew up with a real sense of disconnection because of it. People are authenticity freaks, and if you're mixed you're not 100% anything. And I agree with you, there's been a real shift where people now celebrate the mixed-upness — everyone's a different color and holding hands and everyone's sort of funky and cool and you'd like to sleep with them. That's very prominent in a certain urban metropolitan mindset, but if you go out of the cities there's a lot of fear and resentment toward this mixed-up globalized thing. People are nostalgic for a time that may not have actually existed, when a community was fixed and stable and everyone came from the same place.

What I find funny is that even some people who like the idea of the biracial ethnicity probably still get a twinge of discomfort imagining interracial sex, which is what creates biracial people.

And that's what it really comes down to. If someone sees a mixed race person, in their mind is: who had sex to make you? When people ask me, where are you from? They don't care where I grew up. What they really want to know is, cards on the table, what combination of fucking produced someone who looks like you? Even though we don't have the same on-shore slave history as you have in the States — that Guess Who's Coming to Dinner? stuff — my mom was asked by relatives when she got together with my dad, "Fine, he's a lovely guy, but how will it be when you're pushing a brown baby down the street?' There's this assumption of moral laxity.

Even in the case of Barack Obama, even though a lot of people love that he's from Africa and America because it somehow represents global harmony, I bet a lot of those same people prefer not to think directly about his black Kenyan father having sex with his white Kansan mother.

Absolutely. He's got a nice posterboy family; Michelle Obama is ideal. But I agree entirely, I think that part of it would make people uncomfortable. It's complexity that weirds people out.

n°

| RELATED ARTICLES | |||||||||||||||

|

©2007 hooksexup.com and Will Doig

Commentarium (2 Comments)

"What combination of fucking produced someone like you?" LOLOLOLOLOLO!!!!!!!!!!!

You should probably cite the photograph of the weather underground folks marching. I find this disrespectful of the people in the photo who died for their communist ideas.