[If there's one subject that holds more fascination for film geeks than the movies they've seen or are planning to see, it may be the movies that have not been made and may never will be: the scripts that go into permanent turnaround or excite some interest, only to be abandoned. A few of these attain the status of legends, a process that in the last several years has been exacerbated by the ability to disseminate them through the Internet. Because a screenplay is a physical object but also a blueprint for something fuller and richer, which would probably end up deviating from the script at any number of key points, reviewing unfilmed scripts is a movie critic's form of cryptozoology, kind of like examining a muddy footprint and trying to sketch Bigfoot from it. This week, to kick off our new series dedicated to the unicorns, mermaids, and moderate Republicans of the movie world, the Screengrab looks back at the "Watchmen"-the-movie that might have been.]

When Warner Bros. which owns DC Comics, started looking for someone to adapt its property Watchmen to the movies, it must have seemed a natural choice to call in Sam Hamm, who had written the script for the 1989 Batman, a movie that commercially kick-started the superhero-comic-book movie genre. Hamm's Batman script, which was rushed into production without benefit of the polishing it would have received had not the 1988 Writers' Guild strike intervened, is not without its problems, and if there's a comics convention going on near you, I can introduce you to several people who'd be overjoyed at the chance to list them for you. But it also has Hamm's freshly thought-out take on its hero, which laid the psychological foundation for Michael Keaton's performance and, to a great extent, much of the batlore that's come since.

When Warner Bros. which owns DC Comics, started looking for someone to adapt its property Watchmen to the movies, it must have seemed a natural choice to call in Sam Hamm, who had written the script for the 1989 Batman, a movie that commercially kick-started the superhero-comic-book movie genre. Hamm's Batman script, which was rushed into production without benefit of the polishing it would have received had not the 1988 Writers' Guild strike intervened, is not without its problems, and if there's a comics convention going on near you, I can introduce you to several people who'd be overjoyed at the chance to list them for you. But it also has Hamm's freshly thought-out take on its hero, which laid the psychological foundation for Michael Keaton's performance and, to a great extent, much of the batlore that's come since.

As Hamm would later write, he considered young master Wayne's having elaborately built his life around the murder of his parents and concluded "that Bruce had become Batman as a result of being spoiled. He had grown up with sufficient money and leisure to luxuriate in his own tragedy, to wallow in the false sense that it made him somehow unique. In other words, Bruce had never learned to cut his losses. For good or bad, he'd become addicted to his own pain—and he relied on the outward nobility of his mission to conceal the true perversity of his addiction. In this psychological scheme the Batman persona would function both as a symptom of, and justification for, his madness. To keep it alive, he'd have to relive the death of his parents again and again, killing them anew each night." This sort of talk must have made it seem as if Hamm would be a natural soul mate to Alan Moore, who'd made his name in the American marketplace by applying his own nasty insight to such stock characters as Swamp Thing and the Joker. In fact, Hamm's earliest involvement in the project overlapped with the days when Moore and DC Comics were still on speaking terms, and after Hamm made a pilgrimage to Northampton to sup with Rorshach's creator, Moore declared that he had "complete faith" in him. What neither of them may have grasped is that, whatever Watchmen needed to successfully navigate its way to the big screen, a sharp reading of the motivations of a fifty-year-old pop myth was not among them. Long before Zack Snyder came calling, Watchmen had a reputation for being unfilmable, and watching Hamm try to wrestle it into shape points up some of the reasons for that.

[Please note: while it may seem odd to attach a spoiler's advisory to a discussion of a script that was never filmed, it is impossible to discuss the Watchmen that didn't get made without mentioning the details it shares, and deviates from, the movie that was finally made and the comic book it started out from. Consider yourself warned.]

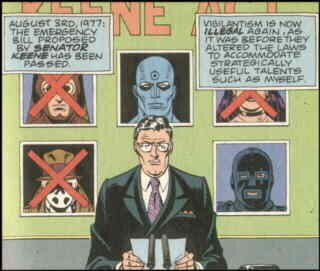

Moore's Watchmen is set in a specific time and place--his fantasy of an America that is a very different place from the America of the 1980s because a repressive U.S. government has had access to a superpowered figure Dr. Manhattan, who was able to keep a lid on things and shut down the cultural and political explosions of the '60s and '70s. It is also a product and reflection of a specific time and place: America in the actual mid-1980s, when it was fashionable to sneer at those explosions and even to try to pretend they hadn't happened. It was also a time when nuclear jitters, exacerbated by the last tremors of the Cold War, seemed to color everything. The first thing anyone trying to adapt Watchmen has to figure out is, what time is it set in, and what version of that time? Hamm's script opens with an action sequence set during the 1976 Bicentennial celbrations. Some terrorists inside the Statue of Liberty have taken hostages and are threatening to kill them and blow up the monument. Riding to the rescue are our heroes, Nite Owl, Rorshach, the Comedian, Silk Spectre, and Adrian Veidt--Moore's Ozymandias, who in an ominous geature is called "Captain Metropolis" here--who have a contract with the government to fight crime and who are banded together under the group moniker "The Watchmen", a name that never actually appears in the comic book. The fact that our heroes actually fight under the handle in the script is our first strong indication that Hamm has a healthy willingness to make drastic changes in the source material to make it fit the new medium. It is also our first strong indication that he kind of doesn't get it.

In Moore's Watchmen, people have been running around in homemade costumes fighting crime since World War II; it's the accidental creation of the omnipotent Dr. Manhattan, whose powers are soon put to service rendering the U.S. government beyond question, that has rendered them obsolete. Hamm eliminates most of the alternative-historical background, so that here, it seems as if Dr. Manhattan's appearance might have inspired others to turn to free-lance heroism, a career option that is shut down after things go dreadfully wrong at the Statue of Liberty. (He also deploys the revelation that Richard Nixon is still president, which Moore announced at the outset of the comic to help set its tone, as a late-inning shockeroo.) Except for Dr, Manhattan's origin story and the revelation of what pushed Rorshach over the edge, Hamm dispenses with Moore's intricate flashback structure. The predecessor versions of Nite Owl and Silk Spectre are gone, and after the murder that announces our jump to 1986, so is the Comedian; he's mentioned in passing a few times (never affectionately) but never seen again, and the news of his special connection to Silk Spectre never arrives. Hamm floorboards it to the end, which even die-hard fans of the comic have been known to concede has always been "problematic." In the original, Adrian Veidt obliterated part of Manhattan to scare the world powers into working together; in Hamm's rethinking, Veidt decides that in order to prevent an apocalyptic Cold War confrontation, he has to kill the indestructible Dr, Manhattan, a hat trick that involves producing some kind of time ripple through which he can prevent Dr. Manhattan from ever having existed, this negating the preceding couple of decades. When he succeeds, the central heroes find themselves deposited, in full costume, in the "real" New York of 1986.

Loopy as all this is--and it is sufficiently loopy to have guaranteed that any mention of the script garners howls of derision from fanboys coast to coast--it's worth keeping in mind just what Hamm was up against. The script, too, is a dated relic from a specific time and place: i.e., a Hollywood where comic book movies were now seen as potential cash cows but not prestige ventures, before Time magazine had included Watchmen on its list of the 100 best novels published since 1923. And the era in which the comic first appeared and the time in which Hamm was cobbling together his adaptation had been separated by its own time ripple: the cordial meetings between Reagan and Gorbachev had effectively killed the nuclear-clock atmosphere that the comic was a part of, even before the Berlin Wall came down. Hamm was taking an instant period piece and trying to find a way to keep it making sense, presumably with a contractually mandated running time of two hours or thereabouts.

In between the new opening and the changed ending, he serves up a sort of Cliff's Notes of the most excitingly filmable moments from the comic, and some of the new details he adds--such as the "Vietnam War Memorial" that resulted from Dr. Manhattan's quick winning of that war, a statue of the big blue bastard cradling a fallen soldier in his arms--catch the flavor of the comic to a T. He also performed a few cosmetic changes on such scenes as Rorshach's origin nightmare, concocting a gruesome new punishment for the masked vigilante to inflict on a child killer. (This was probably a necessary touch, since in a movie, it would be harder to ignore the fact that Moore had stolen the original scene wholesale from George Miller's Mad Max.) Less to his credit, Hamm also had Rorshach making Leno-worthy wisecracks about clogged toilets and street mimes. Even the scenes he retained and did justice to don't mean as much without the background Moore provided, especially since the connective tissue between them and Hamm's altered framework is thin and flimsy. But there's a bigger problem: the changes Hamm made conventionalize Watchmen. Terry Gilliam, who produced another draft with his co-writer Charles McKeown before concluding that there was no way to accommodate all the detail necessary to make a Watchmen movie that would be meaningful and comprehensible in the space of an acceptable running time, complained that Hamm's script just seemed like a bunch of superheroes running around, and he was not wrong.

The script for the current Watchmen movie is credited to David Hayter and Alex Tse. Tse is said to have worked from a pair of efforts Hayter wrote years ago, with an eye to eventually directing the movie himself. Hayter, too, had to grapple with the same road blocks as Hamm, the time period and the ending, and he apparently discarded the former only to have the current team bring it back. The new Watchmen was made according to rules that no one could have anticipated twenty years ago, namely a director with the inclination to make a film that would be as close a physical approximation of the comic book as possible (and the muscle, after the success of 300, to get the studio to go along with him), and a new entertainment business climate full of adults who grew up thinking of the comic as a masterpiece and who'd could envision an audience who'd want it treated not just respectfully but with slavish fan-worship. Confronting Nite Owl at the climax, Adrian Veidt accuses him of "a lack of vision", and that's the problem with any movie version of Watchmen whether the would-be adapter tinkers with the source material or solemnly traces over it. Whatever the billboards insist, it's a vision that somebody else already had, more than twenty years ago.